From the Phnom Penh Post, January 22 - February

4, 1999

The art of saving a nation’s soul

By Sarah Stephens / Photos by Heng Sinith

The painter, Chet Chan

Chet Chan crouches by the brightly colored silk painting

and gazes impassively at the stylized images that dance across the

canvas. To the untrained eye, these beautiful figures seem to represent

a rare and refined side to Khmer art, with their delicate lilting

lines and painstaking detail.

"What do you think? I think it's rubbish. We

should throw it away,” says Ly Daravuth, Professor of Art and

Art History at Phnom Penh's University of Fine Arts. He's serious.

Astonishingly, when he suggests this to Chan. the shy, 60-year-old

artisan chuckles and agrees. This is not some strange publicity stunt.

Chet Chan is a highly-trained craftsman who has survived Cambodia's

various wars, famines and brutal regimes, and is now one of the few

expert traditional painters left in the country. His is a dying craft

but he is determined to pass on the complex codes and secret conventions

of traditional Khmer painting to a new generation. However, the painting

he is studying now was commissioned by a foreigner — a foreigner

who dictated colors, style and subject to the craftsman — thereby

losing the very essence of Chan's art.

"Today, every Cambodian artist does what he

wants. There are no rules," says Chan. "Guidelines and rules

for traditional Khmer painting are very important, especially in terms

of morals and ethics. "Some of the art you see in the shops is

just pornography. Art shouldn't be about this."

Chan only paints scenes from the Reamker, the Cambodian

version of the Ramayana. For more than 30 years he has refined his

technique, studied the artisans who went before him, and recorded

the highly complex codification system that dictates how the characters

and scenes from the Reamkershould be portrayed. In a reverentially

handled notebook, fine pen and ink drawings and extensive notes detail

the titles and images of paintings once found in the Royal Palace,

images now worn away or lost. His, he says, is the only correct record

of these paintings and their techniques.

His sadness is apparent as he describes how the younger

generation of Khmers are not interested in his work. "They don't

know they shouldn't paint sacred images like a god when they don't

know how to paint them. It's only commercial [for them]."

Daravuth is passionate about preserving these traditional

crafts. He is now putting together an exhibition by three of Cambodia's

most respected artisans. "Continuity is the most important thing

for me. These artisans are from a generation of people who still hold

certain values. They are a continuation of a line." There is

now less demand for their work because they are not immediately productive,

he continues. The craftsmen may take months to produce a single piece,

meaning high prices and low output. There is no souvenir stall mass

production here. "The young don't know that the objects [at the

Russian Market] are horrible. There is no model for their generation,"

he says.

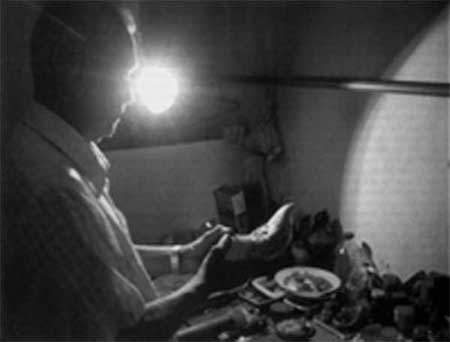

The silversmith, Som Samai

Silversmith Som Samai, 74, knows well the difficulty

of handing down years of experience to younger craftsmen. "I

am teaching my children how to craft silver, but till now I have only

taught them 30 percent of what I know." Samai has worked with

silver since he was fourteen years old, when he answered an appeal

for students at the then newly-formed Ecole des Arts (now the School

of Fine Arts). This was the heyday for his art, he says, before "war

and communism". He is reluctant to condemn the inferior quality

products that flood Phnom Penh's tourist centers, because, he says,

"everything was lost during Pol Pot. I can't blame them. But

I would like to advise them on their techniques".

The mask maker, An Sok

Lacquer-maker An Sok, whose magnificent masks adorn

his home and workshop, says that even his own creations have declined

in quality since the 1960s, because he is unable to afford the expensive

gold leaf needed to decorate the elaborate objects. "People don't

want to buy expensive things now. When something's cheap they'll buy

it."

Phnom Penh residents will have a chance to see the

work of the masters later this month, when samples of silverware,

traditional painting and lacquer masks are exhibited at Situations

Gallery. The gallery, which opened late last year, is the brainchild

of three people: Daravuth; Visiting Lecturer at the Faculty of Sculpture

Ingrid Muan: and Ambassador of the Order of Malta Jacques Bakaert.

While showcasing collections both modern and traditional,

Daravuth hopes the exhibition will play an important role in bringing

traditional arts back into the limelight. "Transmission of knowledge

is so important", he says. "I want to get kids motivated,

to get them to wonder how do you draw a Hanuman figure?" If these

things are not recorded, he says, they will all be lost to history.

But there is hope. There are plans to produce a

series of manuals on traditional painting techniques, and the lacquer

workshop at the School of Fine Arts is about to reopen after having

been closed for years with the help of An Sok's son, who will teach

for free.

For Som Samai at least, to lose those crafts would

be much more than the disappearance of a certain way of life. As he

gently handles his latest creation, a pair of exquisitely carved silver

slippers, he reflects: "We should preserve this craft because

it shows the nation's soul. If you lose that, you lose your nation."

The work of Som Samai, Chet Chan and An Sok will

be exhibited at Situations Gallery, No.47 Street 178 from the 29th

of January.

|