|

|

Making monkeys of men in lakhaoun khaol

By Sarah Stephens

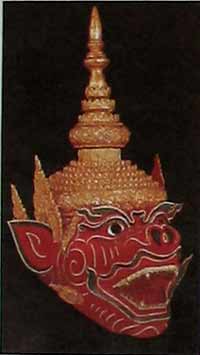

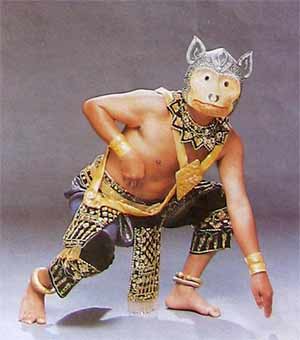

Demonic grinning monkey masks loom down at the visitor, some painted violent red, others icy blue. Intricate designs on the faces are offset by towering gold headpieces, creating a regal yet eerie effect. These are hand-made masks of lakhaoun khaol, a form of Khmer theater, and they are the main draw of a new exhibition opening this week in Phnom Penh, at the newly renovated Reyum Gallery (formerly known as "Situations"). Lakhaoun Khaol, or as it has been translated, "monkey theater", is the name given to a famous section of the Reamker (the Cambodian version of the Hindu epic the Ramayana), where armies of monkeys and demons enact a vicious battle. Dancers mimicking monkey behaviour spring across the stage in leaps and bounds, wearing intricate jeweled costumes and the brightly-painted masks. But the story behind Lakhaoun Khaol is almost as fascinating as the dance itself, and, say the curators, is a key element to the exhibition. "There were two types of Lakhaoun Khaol," says Ly Daravuth, co-curator of the exhibition. "There was firstly what I would call the high version, the court version which was performed at the palace. And then there is the village version, the local performances, which have significant variations." While the court version is the one that most tourists and those living in Phnom Penh will have seen, Daravuth and co-curator Ingrid Muan stress that the village variation is just as important, if not more so, because of its ritualistic meaning. The origins of the dance are unclear, but it is certain that in the nineteenth century, the Royal Palace sent talent scouts out into the provinces to find dancers who could perform lakhaoun khaol, in order to create a royal troupe. Traditionally performed by men only (as it still is in the provinces), the dance eventually became most popular when performed by the Palace's female-only troupe. In the village of Vat Svay Andaet, where the dance is performed annually at New Year, superstitious meaning is attached to the performance, explains Daravuth."The important thing for them is that they believe that they must provide a good performance, and must perform it at the right time, or great calamities will befall the village".

According to villagers, in 1966 a section of the play where characters pray for rain was suddenly answered far too literally. Despite scorching heat and dry weather for many months, in the middle of the performance the heavens suddenly opened, drenching the participants and forcing the cancellation for the rest of the seven-day extravaganza. "And in 1964," adds Muan, "the first four days of lakhaoun khaol were performed in the village, but they then decided to take the rest of the performance to another village. When they returned home, there was an outbreak of cholera, which killed 800 people." Since then the villagers have been careful to prepare the play in exactly the right way, with special ceremonies created to appease the spirits before the play starts. "Villagers go into a trance, and call on the spirits of the demons and monkeys," explains Muan. "The masks themselves are believed to come to life, with the spirits inside them... Gestures are made over their eyes, as if opening them, and finally a mirror is placed in front of the mask so that the spirit can see what it looks like, and who it is." The exhibition features old photographs and descriptions of village-based as well as court-based performances, but the real draw is a set of lakhaoun khaol masks, 30 in all, commissioned for the show and created by master lacquer-maker An Sok. Regular gallery-goers may remember samples of An Sok's work being shown earlier this year in a traditional art exhibition at the gallery. "This is a continuation of the earlier theme," says Daravuth, explaining that the gallery now comprises the whole building rather than just a small section, as before. "We have expanded, so now we are looking much more at the mysteries of the whole performance, rather than just the masks." The exhibition is running from now until the end of the year at Reyum Gallery, Street 178, No 47.

|

|