|

|

Local

Artists are Finding New Ways

|

|

|

|

Above: "Fire and Spirit", oil on canvas, by Soeung Vannara. "There is a common belief that people are formed by combining the four basic elements of water, earth, wind and fire. As long as these elements remain joined together, people live. These elements, however, are only borrowed, and they are slowly given back over a lifetime. With the smoke and ash of their death, people return to the separate elements they once were. When people die because of terrible deeds or torture, what happens to their spirits? My painting reflects on these questions." |

On another huge canvas — made of rough, unfinished paper— a different artist has created a chilling and evocative scene with fine pencil lines. A pile of rubble from an Angkor-style monument tumbles down the canvas, as headless Buddhas and relics litter the scene. Above, a Turneresque clouded sky swirls violently and a shaft of light illuminates a solitary decapitated stone lion. The scene is loaded with powerful emotion— unsurprising, as it was drawn by an artist who himself was orphaned during the KR years.

While many of Phnom Penh's intellectuals, commentators, politicians, and people on the street are busying themselves with news and rumors about the impending KR trial, a small local gallery is tackling the legacy of the KR through previously unexplored channels, with a thought-provoking and unsettling exhibition, "The Legacy of Absence."

"We did not originally plan that this exhibition would be on at the same time as the trial," says show co-curator Ly Daravuth. "All the talk of trials just concentrates on the logistics of putting one on," says Ingrid Muan, the show's co-curator. "But this is a much more accessible thing, it's about emotions and feelings and personal experience."

The show will display the works of 11 artists, ten

Khmer and one from the Netherlands, and comprises part of a much larger

worldwide exhibition on the same themes. American art lover and entrepreneur

Clifford Chanin, of the Legacy Project, has put together a series

of works of art from places as wide-ranging as Germany, Israel, Japan,

China, Bosnia, the former Soviet Union and India-Pakistan. All the

exhibiting countries have one thing in common — they have suffered

a mass trauma or genocide which has left a great "absence"

among the populace. The idea of the exhibition is to try to understand

the kinds of things that are missing after a mass murder or war, and

to explore whether there is a way to fill the emptiness that the victims

leave behind, according to Chanin.

|

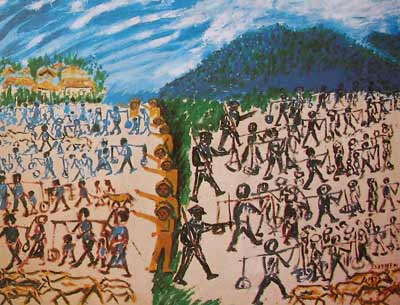

Below: The division of the country (1978), by Svay Ken. from his series of 14 paintings which depict the experiences of his family during Pol Pot's time. This picture shows the division of the country which resulted when the Vietnamese troops entered Cambodia, telling the Khmer people to enter the cities, while Pol Pot's men told the people to go into the forests with them. These paintings are meant to serve as "Records — in particular for future generations — of the time when the people of Phnom Penh were forced into the countryside under the Pol Pot regime."

|

"I am particularly interested in the work of artists because

they are often the first people willing to look at these hard subjects,

and think about the ways in which their works can honor or remember

the people who are no longer present," he says in an introductory

statement.

But the organizers had a shock when they approached Cambodia for entrants, for there is very little that has been explored in the art world here on the theme of the KR. Only Vann Nath, who painted the infamous scenes of the Khmer Rouge in Toul Sleng, and Svay Ken, a local artist who has painted many scenes of the recent past "so my grandchildren know what I went through," have any kind of body of work on the theme. Both are displaying work in the "Legacy" exhibition.

Certainly, the policy of the KR to systematically eliminate intellectuals, writers and artists provides one reason why there is a paucity of original art today. But Daravuth has a further, more considered reason why Cambodia has not explored the KR regime through art.

"The only art works you see on display are the mass-produced paintings of Angkor," he says. "When you talk to the men who produce them, they say they only want to produce beautiful things, that it must be beautiful above all."

Daravuth's view is that the absence of a body of work exploring the KR regime is almost as powerful a statement as if the work had been created in droves. "The people refuse to confront it so far, the artists do not want to contemplate it. Sometimes when you have a shock, you don't want to talk for a while," he said. "They just want to look back with nostalgia and create these Angkor paintings."

Muan, whose mother was living in Germany during the Second World War, says that it also took a while before any significant World War II art appeared there. "There was total amnesia there for twenty years," she said. For the curators, though, it is up to the younger generation to safeguard the legacy of the Khmer Rouge years.

"I am slightly afraid that it is becoming mythologized,

that the personal experiences are being lost to a more general idea

of what happened during those years," says Darvuth. "Just

the other day I was talking to a 20-year-old who had no idea what

the KR sandals [made from rubber tires] looked like. I found it amazing

— just twenty years on, the younger generation are already forgetting."

Many of the paintings in the exhibition have a general feel rather

than being painted from personal experience, but this is something

that will change over time, the curators say, as the artists become

more confident. "It's a first step," says Muan. "They

are now understanding for the first time that it is okay to paint

and discuss these things. As they get more confident more personal

work will be created."

"How do we deal with this heritage?" asks Daravuth, who

himself admits that even though he lived through the KR years, he

cannot get a full, coherent grasp on what happened to him. "With

heritage like Angkor Wat, you have conservationists, the picture painters,

and so on. But with the KR regime, you can't classify it as a UNESCO

world monument --there's nothing there. You have to find another way."

The exhibition, which begins January 11, will run for one month at

Reyum Gallery (formerly Situations), Street 178, in Phnom Penh.

|