|

|

Reamker Revived: New Book and Gallery Exhibition Look to Stir Interest in Ancient Epic

by Michelle

Vachon and Yun Samean

The idea was simple enough, said Ly Daravuth. To

ensure the traditional art of painting the scenes and characters of

the Reamker would not disappear in Cambodia, the hundreds of characters

from the epic tale could be compiled in a dictionary, each with its

own illustration and description. Painstaking work, maybe, but also

a logical way to proceed, thought Ly Daravuth and Ingrid Muan, directors

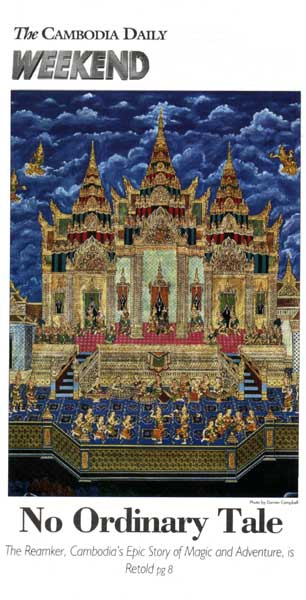

of the Reyum Institute of Arts and Culture. On the same night, the institute opened an exhibition of Reamker paintings - some of which were reproduced in the book - done by the Cambodian painter Chet Chan. They include one painting of the Kailas Palace, or heavenly palace, an intricate blue and gold work on canvas measuring about 3.5 by 2.5 meters. It was commissioned for a private collection and will only remain at the gallery until Monday. Both the book and the exhibition are sponsored by the US-based Kasumisou Foundation.

The difficulties Ly Daravuth and Muan met in the project are reflected

in the title of the book - The Reamker, Painted by Chet Chan.

As they explain in the book's introduction, it is one master painter's

version of the characters. The Reamker has always been a comerstone

of Cambodian culture, and pagodas have traditionally commissioned

artists to paint the epic on their walls, Ly Daravuth said. Each master

painter would draw the story as he had teamed it, coloring the illustrations

with his own style, which he then passed on to his apprentices, Muan

said. As a result, each village and each pagoda had their own versions,

she said. Master painters would hear the story and paint from

memory, based on never-written rules teamed from their own masters,

Muan said. "Hanuman's fur has to be white. But it could be done

in light blue or grey - as long as it looked white from a distance.

It was up to the painter." In addition, she said, "Some

of the 200 characters are interchangeable, especially in the case

of women." A few are unique, such as the fortune-teller Pipaet,

shown with a divining slate. Others may differ in their headdress

or color. Only a fish tail differentiates Mechanub from his father

Hanuman—his mother was Sovann Macha, the queen of the fish.

As featured in the technique section, painting the Reamker is a matter of minute details and infinite patience. To paint a scene on silk, Chet Chan uses acrylic paint and thin gold sheets. He starts with a sketch on paper and transfers it on the silk surface. Next, he covers the sketch with a coat of white, and paints a first series of details in yellow. Using resin from the lovea tree, a type of fig tree, he carefully attaches a layer of gold leaf to the yellow portions of the drawing. Then starts the endless work of painting detail after detail, some so minuscule that they will only be visible up close. Every surface of headgear, clothes and jewelry is covered with fine ornamentation. The muted tones of gold, orange, green, yellow and blue combine to create subdued figures usually shown in movement. "It's very difficult to leam," said Chet

Chan. One has to know the technique as well as the characteristics

of each character, he said. Today's art students have little interest

in traditional art because there is little market for it, said Chet

Chan. Pagodas no longer commission Reamker murals, said Ly Daravuth.

With television replacing story time at night, few Cambodians know

the epic from beginning to the end anymore, said Ang Choulean. Ly

Daravuth and Muan said they hope the book will stir interest in traditional

painting and help keep the Reamker art alive.

The exhibition will run through November. Two conferences will be held at the gallery during the exhibition. On Sept 11 at 5:30 pm, Son Soubert, in Khmer and English, willl talk about the meaning of the Ramayana in Southeast Asia. And Sept 17 at 5:30 pm, Ang Choulean willl discuss the Reamker in daily life in Cambodia in Khmer, French and English. The institute's gallery, located at 47 Street 178, is open daily from 7:30 am to 6 pm. The book is available at the gallery. |

|