|

|

Interpreting Tradition

As Art School Students Explore Techniques

and Develop their Talents, By Michelle Vachon In the 400 or so pagodas he has so far studied, San Phalla has never seen the entire life painted of Buddha's Sovannasam reincarnation. There may be a scene or two depicted—the young man helping his blind parents, or lying near a pond, injured by the king's arrow—but not the story fully told, he said. When San Phalla explained this to the students of the Reyum Art School earlier this year, they decided to turn this into a challenge. Armed with the story, they went about using their imagination to draw episodes of the life of Sovannasam in line with the traditional style used in the country's pagodas for centuries. Three months of efforts later, they had produced a series of paintings, acrylic on canvas, now on exhibit at the Reyum Institute of Arts and Culture, where San Phalla works as a researcher. Detailing the colors of nature, the scenes tell the life of this heavenly being, born to a couple of chaste and religious hermits through the intervention of Preah En (the Khmer name of the Hindu deity Indra). Most episodes are set in the forest where Sovannasam and his parents Bareka and Dukol lived, surrounded by wild animals they befriended. Images filled with greenery and delicate flowers reflect the serenity of their lives spent according to the moral code of conduct The first paintings show the village in which Bareka and Dukol grew up and were married before Sovannasam's birth—peaceful country life among palm-leaf roof homes on the banks of a river. In the last village scene, the couple walks away from their families to become hermits. The following episodes appear on a backdrop of gentle forest tones, except in paintings featuring deities, which are done in gold and sky blue. As the book on the exhibition mentions, Buddha is believed to have

been incarnated 547 times before his last life in which he achieved

enlightenment The 10 lives prior to this last one are especially well-known

in Southeast Asia; their stories are called the 10 Jataka, or Cheadok

in Khmer. The Sovannasam Cheadok describes the third of these lives.

In Cambodia, the most painted of these 10 Cheadok is the one about Buddha's

life just before his last reincarnation; the others only get occasional

attention.

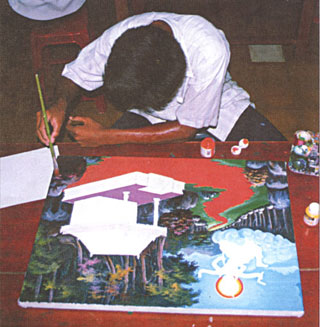

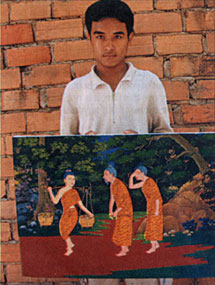

The ongoing research San Phalla is conducting with funding from the Toyota Foundation, and which he had started while attending the Royal University of Fine Arts, shows that the style in pagoda paintings has been changing over the years. Before the 1940s, painters would recreate stories in great detail and with numerous characters, he said. They often would do the work for free, as their contribution to the pagoda to acquire Buddhist merit, and would use natural dye, which produced a muted effect and lasted a very long time, he said. Today, painters try to quickly cover as much wall surface as possible since they are paid $13 to $15 per square meter, said San Phalla. Characters are few and huge; for example, a marriage scene may only feature the bride and groom, he said. Painters use chemical paint and very bright colors, which quickly fade and peel off the walls. The whole approach to pagoda paintings also seems to have changed. Before the 1940s, the names of people paying for the work might be written discreetly, if not entirely omitted, said San Phalla Nowadays, their names are always put in the decorative border or directly on the paintings, he said. Portraits of the donors are often incorporated into paintings, at times filling as much space as the religious scenes themselves. For their Sovannasam Cheadok series, students of the Reyum Art School had to come up with an appropriate traditional Khmer style. At first, it looked easy to paint, said Phe Sophon, 19, who painted Bareka and Dukol leaving their home village. But then, the fine details that are part of traditional style made it much more difficult than he anticipated, he said. Students had picked the scene they wanted to bring to life. Hout Vannak, 18, had chosen the episode in which the kinnari, or mythical birds, take Sovannasam to a spring to bathe. "I thought it would be a beautiful moment and scene to paint," he said Younger students at the school also painted their interpretation of the Sovannasam Cheadok, but in their own styles. To illustrate the celestial architect conjuring a hermitage for Bareka and Dukol, 10-year-old Mom Sophon drew light rays coming out of a hand pointing to a home that looks more like a temple. The school was open three years ago to help disadvantaged young people

develop new interests and skills. Some of them are street children with

or without families and others who have fathers driving cycles or motorcycle

taxis, said director Lim Vanchan. About 80 percent of them also go to

regular schools, he said. The 120 students are divided into four classes

of varying skill levels running on a full-time school schedule. The

training covers drawing from life, traditional Khmer ornamentation and

works of imagination. The school was not meant to form artists, per

se, said Mark Rosasco of the US-based Kasumisou Foundation, which funds

the Reyum Institute and school. "We wanted to give young people

skills, and help them get a sense of pride and of their own Cambodian

identity through the arts," he said. "But it has been a shock

to all of us how economically minded kids already are," said Ingrid

Muan, co-director of the Reyum Institute. "They want to leam something

to earn money." Their needs and goals have been dictating some

of the school's activities. For example, Reyum has been trying to find

commissions for its highly skilled older students to work as a group.

Already, they have painted the mural on the outside wall of the National

Archives building, for which they designed a traditional Khmer pattern

of brown on beige. Proceeds from the sales of the students' paintings

will go toward supporting the school's activities. The exhibition runs

through the end of August. |

||||||

|

|